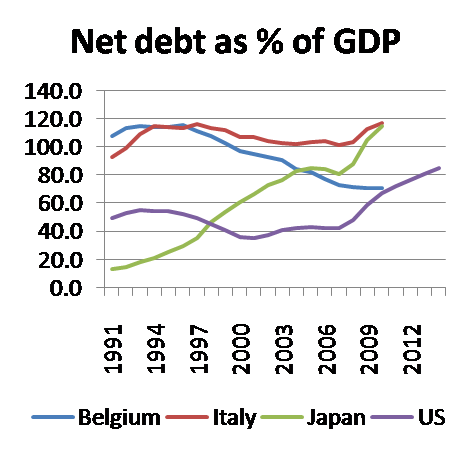

One question that keeps coming up is, how can I reconcile my scorn for warnings about bond vigilantes with what is happening to Italy? This seems especially pointed because I have in the past used Italy’s ability to carry debt exceeding its GDP as an illustration that debt concerns were overblown.

The key point is that by joining the euro, Italy took a bite of the apple — it converted its advanced-country status, as a nation issuing debt in its own currency, into original sin, with debts in someone else’s currency (Europe’s in principle, Germany’s in practice). That is the root of its new vulnerability.Here is the alleged chart Krugman is defending his use of:

And the sinker:

Italy is politically weak because it’s Italy. If these countries can run up debts of more than 100 percent of GDP without being destroyed by bond vigilantes, so can we.Of course this type of reasoning was wrong judging by these awesome bond yields:

Italy

Mish explains:Today's euphoria is about falling yields on Italian government debt. The yield on 10-Year Italian bonds is down 44 basis points to 6.45%. The yield on 2-year government bonds is down a whopping 70 basis points to 5.70%.While this likely ECB intervention in the markets brought some short term relief, it won't last long. The truth of the matter is this: Krugman said that Italy's high debt didn't bring the bond vigilantes out in droves. He was right at that point. Now it has so it turns out much to his dismay, high government debt does drive bond yields up. Was it a contraction? Yes and no. In the literal sense, no, since Krugman was describing that period in 2009 when Italy had accumulated a large amount of debt but could still borrow on reasonable terms. But the way Krugman spoke, and the way he refers to the U.S. today, is that the high debt can go on without the bond vigilantes jumping in. That clearly isn't the case for Italy anymore.

And this brings us to the key takeaway from his column today in NYT:

What has happened, it turns out, is that by going on the euro, Spain and Italy in effect reduced themselves to the status of third-world countries that have to borrow in someone else’s currency, with all the loss of flexibility that implies. In particular, since euro-area countries can’t print money even in an emergency, they’re subject to funding disruptions in a way that nations that kept their own currencies aren’t — and the result is what you see right now. America, which borrows in dollars, doesn’t have that problem.Money printing; it always comes back to money printing for mainstream economists. The EU's lack of being both a fiscal and monetary union is the problem as some countries (Germany mainly) strangely object to money printing to fix the crisis. These situations historically always break up as will the Euro zone. You have heard it all before and it continues to be hammered down the public's throat. Portugal's President has joined in the chorus today, via Bloomberg:

The European Central Bank can stop the spread of the continent’s financial crisis with “foreseeable, unlimited” purchases of Italian and other government bonds, Portuguese President Anibal Cavaco Silva said.

“The European Central Bank has to go beyond a narrow interpretation of its mission and should be prepared for foreseeable intervention in the secondary market, not as the central bank has done up to now,” Cavaco Silva said yesterday in an interview at Bloomberg headquarters in New York. He said government leaders are unlikely to move fast enough to find solutions.

“It has to be able to be a lender of last resort,” said Cavaco Silva, 72, who as Portugal’s prime minister presided over the 1992 signing of the Maastricht Treaty, which cleared the way for the euro common currency. “It has to be a foreseeable, unlimited intervention.”(my emphasis)Despite the ECB putting interest rates at below market levels (I, as well as others, assume as much judging by the amount of debt held by the PIIGS) money isn't being printed fast enough to offset the debt crisis in Greece, Portugal, etc. Again, nothing new here. Martin Wolfe, echoing the solutions offered by Nouriel Roubini, says much of the same, via Financial Times:

Mr Roubini discusses four options for addressing these stock and flow challenges simultaneously: first, restoration of growth and competitiveness through aggressive monetary easing, a weaker euro and stimulatory policies in the core, while the periphery undertakes austerity and reform; second, a deflationary adjustment in the periphery alone, together with structural reforms, to force down nominal wages; third, permanent financing by the core of an uncompetitive periphery; and, fourth, widespread debt restructuring and partial break-up of the eurozone. The first could achieve adjustment, without much default. The second would fail to achieve flow adjustment in time and so is likely to morph into the fourth. The third would avoid both stock and flow adjustment in the periphery, but threaten insolvency in the core. The fourth would simply be the end.The first option would be default because as each new euro is printed, the principle of the debt needed to be paid back is lessened in value. The third is just mumbo jumbo for government stimulus offset by money printing. The second will lead to the fourth and the fourth option is exactly what needs to and what will happen.

So here we are at the core solutions yet again: offset high debt with money printing. Money printing (enriching banks at the expense of the middle and lower class) is all central banks have in the end. It is the last resort of fools who think they can dictate the economy by simply moving a few chess pieces around. What will become of the Euro zone will all come down to the German citizens as they decide whether to lay down like a back-alley dog and keep taking kicks to the rib cage or whether to get up and fight back. The latter will happen one way or another, it just depends on how soon.

Also be sure to check out this good interview with Jim Grant as he explains the dangerous leverage the ECB and Fed have accumulated. Here are the takeaways:

The ECB has expanded its balance sheet mightily under Trichet. We have a new leader and we have a new imperative. I dare say Europe is going to print money.

The Italian yields did not fall on their own. It raises questions of overall integrity of market prices. In the US the Fed has nationalized the yield curve. In Europe much the same is going on: the SNB is expanding its balance sheet at astonishing rates of speed. The world over there is seeing immense money printing and there is a huge race to debase on the behalf of the sponsors of paper money.

The ECB has a ratio of non-AAA rated assets to equity of 14 to 1. What the ECB has been doing is stepping in where private money fears to tread. In the private sector we call the heading for trouble... The New York Fed is leveraged 100 to one.

I would imbed the video but Bloomberg interview have a nasty habit of being on auto play which I haven't been able to figure out how to adjust yet. The SNB comment is very interesting, I will definitely have to look into it at some point when I have a waking minute to do something besides work and write.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar