After years of litigation, the United States government, along with the governments representing the fifty states, has reached a joint settlement with the country’s five major banks and mortgage lenders over their questionable practices of mortgage foreclosure. Via Financial Times:

US regulators are preparing to announce a settlement, worth up to $39.5bn and covering nearly all 50 states, that would resolve allegations that five leading banks systematically abused borrowers in their pursuit of improper home seizures.

Under the proposed agreement, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Ally Financial would be forced to improve their mortgage procedures; reduce borrowers’ loan balances and monthly payments; and make about $4.2bn in cash payments to an estimated 750,000 aggrieved homeowners and state governments, people with knowledge of the matter said.

In exchange, officials would promise not to pursue certain mortgage-related legal claims against the targeted banks.From an austro-libertarian perspective, this settlement can be looked at in a variety of ways. Depending on your view of the legitimacy of government, federal regulators and state governments filing suit over fraud in mortgage practices or wrongful foreclosures could be seen as the correct avenue to pursue. This is especially so for minarchists and classical liberals who see the state as justified in righting instances of fraud. For those of the more anarchist or Rothbardian variety, legal arbitration such as this can be handled by private courts, enforcement, and even company directed boycotting. Whatever the case, if the banks were in the wrong, than the rule of contractual law dictates concessions to be paid toward the victims.

Unfortunately, the foreclosure mess and infamous robo-signing scandal is anything but a simple, black and white issue to resolve. In fact, the Federal Reserve, in a report release almost a year ago, found no evidence of wrongful foreclosure practices by the big banks. Given the Fed’s, let’s just say “close,” relationship with the financial sector, some discretion should perhaps be applied when considering the report. And it’s precisely because of this public-masquerading-as-private affiliation between the mortgage market and federal government that the housing bubble was exacerbated and the process of sorting through the jumble has been met with so many roadblocks.

In the Ethics of Liberty, Murray Rothbard points out that, “the perfectly proper thesis that private persons or institutions should keep their contracts and pay their debts.” But according to Doug French,

the mortgage market is anything but private. Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, in its May 14, 2010, edition points out that Fannie, Freddie, and the FHA “accounted for 97% of new mortgage lending in the 50 states. That is, they either purchased or guaranteed all but 3% of new homes secured by American dwelling places.”So much for the mortgage market being a product of private, and thus purely market, forces. When looked at through the lens of private vs. public, the government’s settlement with the big banks ends up being an exercise of preserving the status quo under the guise of appearing to be doing something. As Yves Smith of Naked Capitalism shows, this settlement deal really isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be:

The total for the top five servicers is now touted as $26 billion (annoyingly, the FT is calling it “nearly $40 billion”), but of that, roughly $17 billion is credits for principal modifications, which as we pointed out earlier, can and almost assuredly will come largely from mortgages owned by investors.The settlement hardly puts a monetary dent in the balance sheets of the prosecuted banks; another sign that the deal is simply a farce and a handy tool for President Obama to wave around when campaigning for reelection.

That $26 billion is actually $5 billion of bank money and the rest is your money. The mortgage principal writedowns are guaranteed to come almost entirely from securitized loans, which means from investors, which in turn means taxpayers via Fannie and Freddie, pension funds, insurers, and 401 (k)s.

That $5 billion divided among the big banks wouldn’t even represent a significant quarterly hit. Freddie and Fannie putbacks to the major banks have been running at that level each quarter.

In the sphere of ethical law, aggressive violations of property rights and commitment of fraud are to be prosecuted. The state however doesn’t play by those same rules as it yields coercion over a given citizenry and commits fraud on an almost daily basis either through taxation, currency debasement, or just plain use of public funds for the purpose of enriching politicians and their friends. With the Federal Reserve System overseeing the whole of the banking sector, banks “should really be seen as a highly regulated public utility” according to Don Luskin of Trend Macrolytics. This says nothing about the enormous amount of money some firms use to finance the campaigns of their preferred Congressmen or Presidential candidate who in turn legislate on their behalf.

The real danger behind this foreclosure settlement is that it’s a perpetuation of the moral hazard which plagues the financial industry and the lifeblood of the economy. Though the evidence is shoddy, there are no concrete examples of wrongful foreclosure of those who were making their payments on time. The string of foreclosures appears to have emanated from those who couldn’t work out a reduction of their principal owed as their house went underwater due to a fall in home prices. This settlement simply amounts to a bailout of those who can’t afford their mortgages and haven’t been making payments. Dick Bove of Rochdale Securities explains why in a CNBC interview:

The talking heads here miss the dominant issue within this whole mess: the fact that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy, aided by the housing policy of the federal government and its GSEs, created the housing bubble to begin with. Had interest rates not pushed down to unprecedented levels at the beginning of the 21st century, the housing market would not have experienced such an inflationary boom. The mortgage foreclosure crisis is only a byproduct of the central planners at the Federal Reserve. Once the core dilemma of continual fiat boom and bust is recognized and put and end to, widespread calamities such as wrongful foreclosure lawsuits are more likely to be contained in the future.

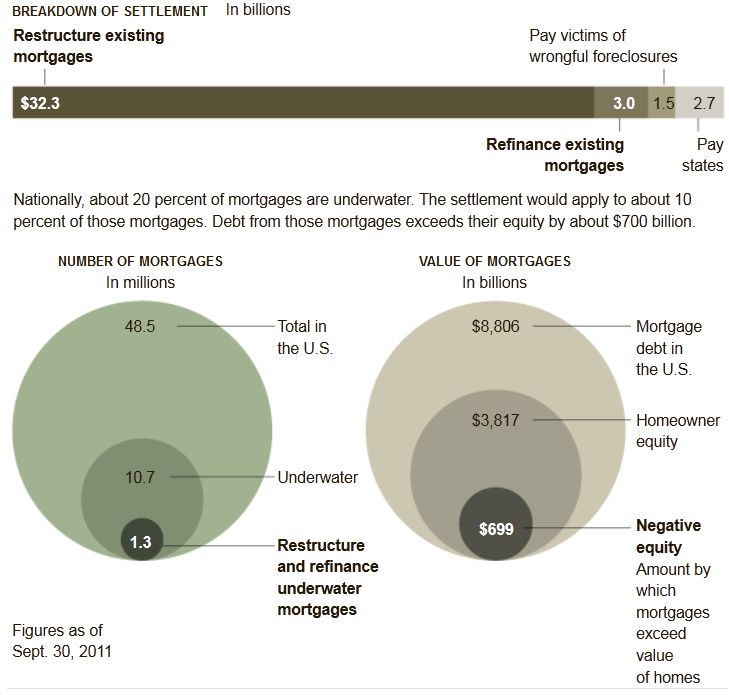

If interested, here is a breakdown of the settlement payout via the New York Times/Big Picture:

Here is another breakdown via FT:

Nationally:

- – Servicers commit a minimum of $17 billion directly to borrowers through a series of national homeowner relief effort options, including principal reduction. Servicers will likely provide up to an estimated $32 billion in direct homeowner relief.

- – Servicers commit $3 billion to an underwater mortgage refinancing program.

- – Servicers pay $5 billion to the states and federal government ($4.25 billion to the states and $750 million to the federal government).

- – Homeowners receive comprehensive new protections from new mortgage loan servicing and foreclosure standards.

- – An independent monitor will ensure mortgage servicer compliance.

- – States can pursue civil claims outside of the agreement including securitization claims as well as criminal cases.

- – Borrowers and investors can pursue individual, institutional or class action cases regardless of agreement.